To Avoid A Prolonged Depression, Pass Medicare for All Immediately

The United States faces a health crisis of its own making, set to collide headfirst with the pandemic

Outside of the coronavirus itself, the biggest looming public health threat in the United States is the state and local budget cuts that experts have been warning about for months. In June, a National League of Cities survey found that 74% of municipalities had already made cuts in their spending. In this post I will explain why cuts to state and local budgets will create a disastrous set of downstream effects that will succeed only in prolonging the deleterious economic effects of the coronavirus pandemic, and in negatively effecting overall population health to nearly incalculable proportions. Congress can act to swiftly stem these adverse effects by passing and quickly implementing a federal universal single payer program, Medicare for All.

By far, the single largest line item on any state budget is healthcare spending. States spend this money in a variety of ways, but the most well-known is the Medicaid program. Even compared to its federal counterpart Medicare, Medicaid is a vast and byzantine set of programs and has a unique implementation in each U.S. state and in five U.S. territories. Broadly speaking, Medicaid exists for the explicit purpose of providing medical care and assistance to the poorest and least privileged among us. This has unfortunately not stopped lawmakers at every level of government from interpreting this mandate as a reason to hyper-target the program and impose burdensome restrictions on who qualifies for assistance and who does not.

Depending on the state or territory you live in, you may be required to hold a job, and prove that you have held your job, in order to maintain benefits (the final state to suspend these requirements due to the pandemic, Utah, did not do so until April 2nd of this year). If you are permanently disabled you may be required to submit to periodic check-ins by a state Medicaid representative to prove you are still disabled. The set of administrative burdens across Medicaid implementations is so vast that it is not particularly conceivable to digest in the scope of this post. For further information on just how loathsome implementations of this program have become, I highly recommend the scholarship of Jamila Michener and of Pam Herd and Don Moynihan.

Medicaid’s countercyclicality is a death sentence in a pandemic

States do not pay for this program alone. The federal government contributes an amount of matching dollars to states to fund their Medicaid programs. This matching amount varies in percentage state by state, but is always based on dollars that have been spent, rather than an amount necessary to maintain assistance for all who need it. This is one of the fundamental issues with Medicaid. During an economic downturn, more people become unemployed or lose income or assets that states draw from as tax revenue. As people lose income and assets they become more likely to require basic government assistance for things like healthcare, which is exactly where Medicaid is meant to step in. This is what people mean when they refer to healthcare as countercyclical: as the economy worsens, healthcare needs tend to rise. It takes no stretch of the imagination to understand that this system does not present ideal circumstances for dealing with an economic downturn brought on by a global pandemic.

That this is an issue with state budgeting for health expenditures has not gone unnoticed among legislators. These conditions are precisely why the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES) included minor increases in federal matching funds to Medicaid. Many critics have rightly pointed out that increasing federal funding in this way is insufficient, yet few go so far as to call for the federal government to fully fund state Medicaid programs (or healthcare for all, for that matter) for the duration of the pandemic and the linked economic depression. And in the mean time, states are left footing the bill for an increased amount of Medicaid enrollments and a decreased pool of revenue with which to pay for their care.

Unfortunately, even if the federal government fully took on states’ Medicaid funding, it would be a massively inefficient way to accomplish what the actual goal here should be: protecting the health of the entire population during the pandemic. This is because in addition to the administrative burdens outlined above, which vary state by state, all Medicaid programs are means tested. In practice, this means that in each state or territory it is up to the applicant to show that they have an extremely low income, and that they have less than a certain amount of “countable assets.”

Medicaid means testing and asset limits have given rise to what has become known as the “Medicaid spend-down” in the United States. This term, which I assume may horrify readers outside the United States, refers to an intentional process undertaken by an individual to sell property they may own or spend money they may have until their assets are below the state’s qualification limits for Medicaid enrollment. People do not undertake this lightly. A Medicaid spend-down is often the last resort of someone who is disabled or desperately ill, as mounting healthcare costs from private insurance begin to make them have to choose between their own healthcare and the ability to afford food or shelter.

With nearly 50 million new unemployment claims in the last 16 weeks, and those who had employer-sponsored health insurance finding themselves needing to get health insurance through the exchange markets or through Medicaid, it is highly likely that many people are now having to make this exact decision. Add to this that federal Unemployment Pandemic Compensation (FUPC, the $600 federal UI boost) is set to expire July 31st, that an estimated 30% of Americans missed their rent payment in June, and that a new study shows at least 5.4 million people lost their employer-sponsored insurance between February and May. By August it is likely that even more people will come to realize that their only hope to maintain necessary care will be to do a Medicaid spend-down.

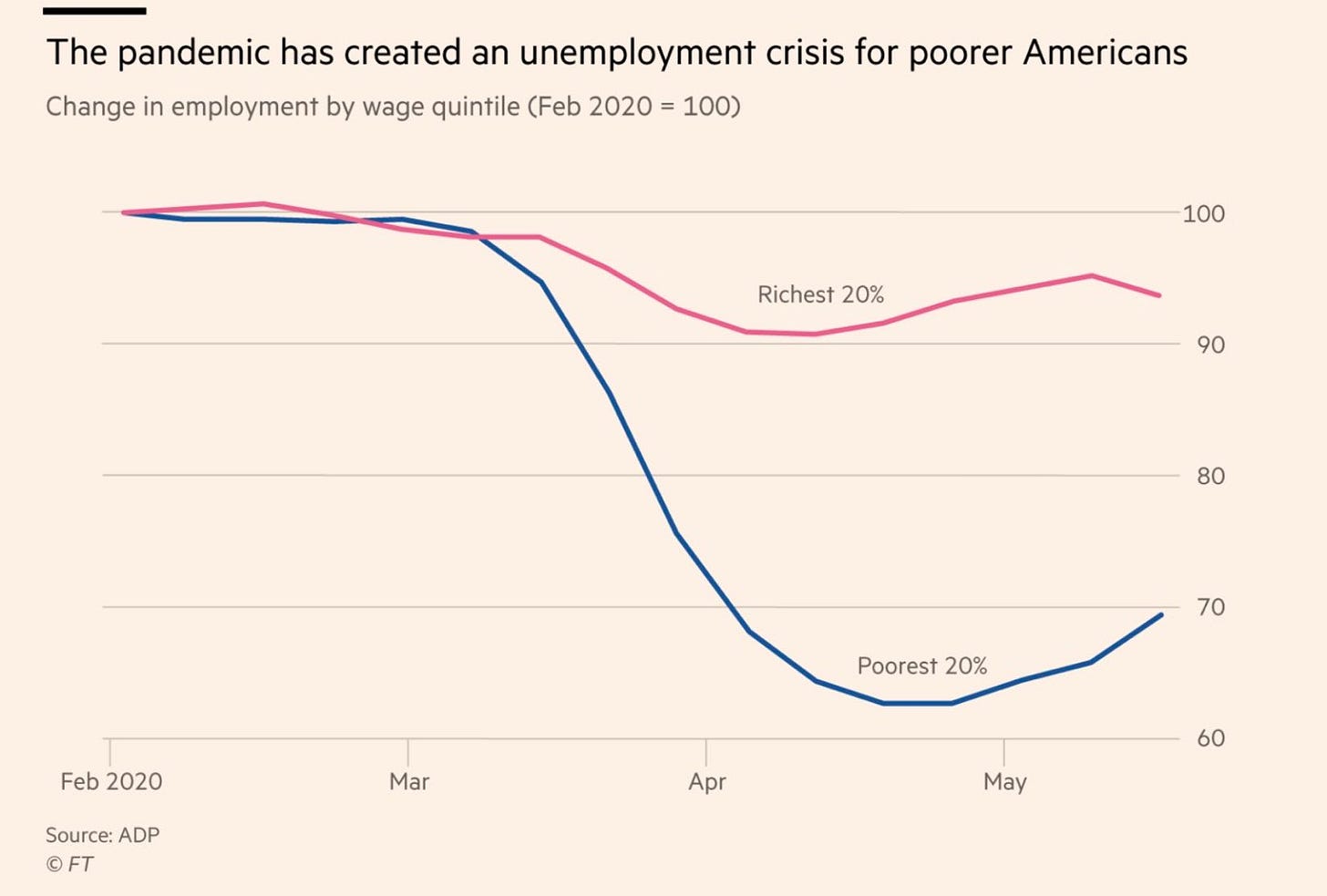

This is a critical issue that has gone largely unremarked as the pandemic has worsened in the United States. It isn’t merely enough to reopen the exchanges, because many people needing to rush to buy a market healthcare plan may only be able to afford one because of their FUPC benefits, which are expiring. It isn’t merely enough to have the federal government pay for COBRA, when we know that unemployment has disproportionately hit the low end of the labor market, who are much less likely to have employer-sponsored insurance in the first place.

It isn’t merely enough to fully fund state Medicaid programs, because for many by the time they have reached such financial hardship that they qualify for Medicaid, their lives may have been irreversibly ruined. Even then, there is no telling when the state they live in may choose to re-impose work requirements on Medicaid, despite the pandemic. (Congress has attempted to head off this possibility by including “maintenance of effort” requirements in the CARES Act, but one can easily imagine many possibilities for states to find creative ways around them).

Even then, a Medicaid spend-down is not instantaneous. Whatever the new enrollment figures are now, it is likely that many people are still in the process of completing their spend-down and collecting the necessary documentation to have their assets certified by the state as qualifying. Expect new enrollments in Medicaid to balloon as people complete this process, and as others learn that a “spend down” is their only hope. That this is some people’s only hope is not hyperbole—for many people in America the next insulin dose, the next Remicade infusion or Humira injection, the next refill of PrEP, the next dose of T or estrogen, is the difference between life and death.

But how are you going to pay for it?

Longtime listeners of Death Panel, the podcast I co-host, will know that the above header is a joke. The federal government has the power to finance anything it wants, and the federal budget itself that both Democrats and Republicans like to moralize about is a fiction created in 1974.

With that being said, state budgets are largely a different story (while they don’t necessarily have to be, that is not an argument within the scope of this post). By and large, states have set rules for themselves which prevent them from deficit spending, which itself tees up the issues with Medicaid spending in a point of crisis as outlined above. Because of this, states are in a massive bind: recall that states’ biggest expenditure by far is healthcare.

It is instructive to look to these state budgets and compare the amount states spend on Medicaid programs to early projections of their expected revenue shortfalls due to the coronavirus pandemic. (Due to revenue projections being indeterminate by nature, and the inconsistencies with which these numbers are arrived at on a state-by-state basis, I won’t claim to be offering any kind of concrete proof here. However, if the coronavirus pandemic has taught us anything so far it is that we have vastly underestimated the economic and health impacts of the virus on the United States, so I feel confident in looking to these figures).

The two main datasets I’ll be looking to for this are the National Conference of State Legislatures’ (NCSL) COVID-19 Revised State Revenue Declines list (as of July 7) and Pew’s data on Medicaid own-source revenue. (As mentioned above, the federal government pays part of the cost of all Medicaid programs, at a minimum of 50% matching funding. “Own source” means this is money the state is paying for Medicaid out of tax revenue it has raised itself, rather than with federal support).

In comparing these figures it becomes immediately clear that many states could have their projected budget shortfalls made up for—and then some—by making state Medicaid funding redundant through a Medicare for All, single payer program. Many states whose projected budget shortfalls are not completely made up for would still see significant reduction in their shortfall, which they are likely to otherwise make up for through draconian cuts to social services.

Colorado, for instance, spends about 18.3% of its revenue on Medicaid, and is expecting a 5% budget shortfall in fiscal year 2020. If this funding were made redundant through a Medicare for All program, the state’s projected budget shortfall would be completely absorbed, and a full 13.3% of its annual budget could be freed up for the expansion of other public programs.

Kentucky spends 13.5% of its revenue on Medicaid and expects a 4% budget shortfall for FY 2020, followed by an 11 to 17% budget shortfall for FY 2021. In this instance, a single payer program would absorb the entire FY 2020 budget shortfall with 9.5% of its entire budget to spare. This could be used to expand other public programs, or carried forward to absorb the FY 2021 budget shortfall from the coronavirus depression, should Kentucky’s shortfall in that year grow beyond 13.5%.

Not every state would see their budget shortfalls curtailed, and not every state and territory has had shortfall projections published. But it is clear that a significant amount of states would see the revenue impacts of the coronavirus depression absorbed by such an action, including leaving additional revenue for them to utilize for programs against the pandemic. For data on FY 2020 alone: Pennsylvania would have its projected budget shortfall absorbed and an additional 13.2% of its budget opened up for other spending. Louisiana would see its budget shortfall absorbed and an additional 19% of its budget open for other spending. Iowa would see its budget shortfall absorbed with an additional 9.2% left over. Rhode Island would see its budget shortfall absorbed with an additional 18.4% left over. I’ll include the full table at the bottom of this post, but again keep in mind that these are estimates based on state projections.

(I’ll also note that the figures above are obviously a counterfactual. They assume a fully federally funded Medicare for All program was implemented at the outset of fiscal year 2020 and states did not adjust their taxation accordingly. For our purposes however they remain a significant demonstration of our main point, and suggest how federal universal single payer could completely change states’ relationship to funding other public services.)

A cure past the pandemic

Perhaps the bigger question at issue here is this: do states really want to have their biggest budgetary line item be what is in essence an insurance program of last resort? It’s clear that a swift transition to a Medicare for All program could help the states above avoid cuts to other critical programs like education or social services in response to the coronavirus depression, in a significant number of cases leave them with extra discretionary room to respond to the pandemic without having to look for new revenue sources. But beyond the pandemic, at the long end of a recovery if little systemic change is achieved, what these figures really illustrate is how much more states could already do if the federal government covered healthcare for all. As Suzanne Mettler has noted, as the cost of Medicaid has grown states have reduced the amounts they invest in higher eduction. Mettler cites that funding Medicaid is a requirement for states, whereas education and other programs are deemed discretionary.

Above: detail from Andrew Cuomo’s … interesting … New York State COVID-19 memorial poster

The future of health funding in New York is a great example. I tend to like this example in part because New York became known as the epicenter of the pandemic’s spread in the United States (though this narrative largely ignores what happened in Washington state), but also because despite the amount of money the state spends on healthcare there is still a large movement pushing for the state to enact its own single payer system. Such a demand must come from somewhere, so it is safe to assume that this means even a big blue state helmed by coronadaddy Andrew Cuomo is not meeting the health needs of its population, despite spending 28.7% of its budget—the highest of any state—on own-source Medicaid funding. Also, Governor Cuomo has signaled that single payer should happen at the federal level, and despite his eagerness to push Medicaid cuts at the outset of the pandemic, I would like to make sure he never forgets he said that.

New York’s projected budget shortfall varies by some estimates. Gov. Cuomo has said to expect the state to see a $61 billion revenue shortfall between fiscal years 2021-2024, roughly $20 billion per year. According to the data from NCSL we’re citing above, New York expects a 13% budget shortfall in FY 2021. This means a Medicare for All program would absorb New York’s entire projected budget shortfall, leaving a full 15.7% of its budget left over to redistribute to New York’s tragically underfunded public schools and other social programs.

If we do nothing, then if history teaches us anything shortfalls like New York’s will be made up for by as extreme of austerity measures as you can imagine, potentially including the permanent loss of critical functions undertaken by the state.

So, let’s say we pass comprehensive, federal universal single payer. As I said above, Congress would still need to take swift and dramatic action to make sure that many states do not have to make cuts to critical social services that are already in dire need of further support. But one can say with certainty that if Medicaid were made redundant by a universal, free at the point of service Medicare for All program, it would certainly massively contribute to stemming the pain of a coronavirus depression. And instead of facing administrative burdens, paperwork requirements, or questions of whether your insurer covered X or Y drug, everyone would just be covered. More than that, even if states wanted to hew to their hardline stance of budgetary restrictions, some could look to the freed up space in their current budgets as an unprecedented opportunity to do the reverse of austerity in the middle of a pandemic: invest in public services. Maybe feel truly emboldened to actually fight the pandemic.

There are many ways you could use better federal spending to fight the pandemic, but immediately enacting Medicare for All (specifically the Pramila Jayapal-introduced version, if not a more robust version with a shortened implementation window) is certainly one of the most elegant. A study in the Lancet showed that enacting Medicare for All could save 68,000 lives per year—and that was before the pandemic. With Congress presenting only uncertainty in the face of the pandemic, and states left to figure out how to act in the meantime, we must pressure legislators to pass Medicare for All immediately, with an implementation period as swift as possible. Anything less and we’re likely to see countless people fall into not just a spend down, but a death spiral.

Artie Vierkant

—

Thank you for reading Health and Capital. As I mentioned in my introductory post, if you enjoyed this and would like to support my ability to produce future posts, please subscribe, share links to it, tell me what you think, and become a patron of the Death Panel on Patreon. Death Panel is a podcast I co-host with Beatrice Adler-Bolton, Philip Rocco, and Vince Patti, and if you enjoy Health and Capital you will probably enjoy it as well.

My thanks to Philip Rocco for invaluable notes on this post and for pointing me in the right direction to dependable data sources for the above comparison. And major thanks also to my first paid subscribers. As I grow comfortable with the format I’m planning to have the first few weeks of posts guaranteed to all be free for all to read and access, and will introduce premium posts as it seems appropriate. So for the moment please see paid subscription as a show of support and encouragement to continue and develop this project. Note also that future posts won’t always be as data-oriented as this. Many of the issues I expect Health and Capital to cover are fundamentally political in nature and won’t require a fallback to spreadsheet socialism to advocate for.